08/17/2018

Imagine you’re a highly competent mid-level manager with years of experience of successfully delivering projects. Based on your track record, you’re asked to manage a challenging project that has faced issue after issue. One of your direct reports on this project, Jane, is a rising star in the company and someone who considers you a mentor. Another direct report, Jill, has a history of being difficult to work with and sometimes exhibits stubborn behavior. It is a stormy Thursday afternoon and Jane and Jill come to you to pitch different options on a path forward for the project. As they pitch their ideas, you take some notes, ask clarifying questions, and ultimately you decide to move forward with Jane’s idea.

EVERYDAY BIAS

All of us are subject to the biases of other people and we all employ biases of our own, often unconsciously, that impact us at work. One of our daily business interactions most fraught with biases is decision-making. Behaviorists, whether in the field of psychology, economics, or finance, will tell you that the weather, the time of day, the person delivering the message, your own desires for the message deliverer’s success or failure, and many other things can impact how you receive the message. Many of these were present in our imaginary depiction above, but you were likely as unaware of their importance then as you are when you are making decisions in reality.

Additionally, Prospect Theory tells us that people tend to feel more pain from losses than joy from gains, so people often seek to minimize loss rather than maximize gain. This is in stark contrast to more classical models of economics, like Expected Utility Hypothesis, where everyone is a rational economic agent (homo economicus), utility maximization is the main goal, and utility functions are generally assumed to be linear. Given this disparity, how can we ensure we acted rationally in picking Jane’s idea over Jill’s and weren’t just trying to spare ourselves what we expected to be a greater cost of mental energy by going with Jane’s idea?

We all employ biases of our own, often unconsciously, that impact us at work. One of our daily business interactions most fraught with biases is decision-making.

HOW WE THINK

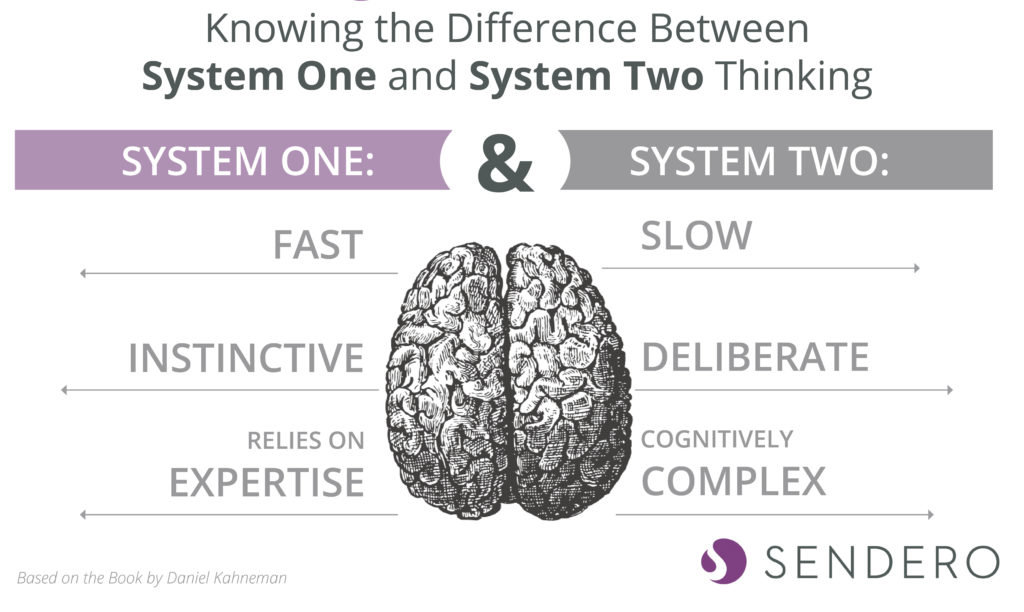

In Nobel-prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow, he discusses two systems of thinking. The first, “System 1”, is fast, instinctive, and relies on our expertise. The second, “System 2”, is slow, deliberate, and logical. This use of System 2 thinking is relatively intuitive for us – as is knowing whether to use System 1 or System 2.

As we gain experience, and ultimately expertise through repetition, our brains build tools to help us act more quickly – we recognize shapes, patterns, and groups in things and actions. Most “instinctive” action in sports – for example strikers in soccer diving toward the goal to knock home a rebound – is a result of this System 1 thinking of relying on our brain’s ability to recognize the shape of the defense, the complex geometry of where the goalie is in relation to the shot that is being taken, and our understanding of that goalie’s capabilities. Instead of actively processing each of those pieces of information, the skilled striker just knows when and where to move.

Similarly, late in a tied basketball game, a coach might call a timeout specifically to break his or her team from System 1 thinking and shift over to System 2 thinking. By bringing action to a halt, the coach allows themselves the ability to deploy more complex cognitive tasks – a specific play out of the timeout and then a specific action for a make and another action for a miss, all of which are then executed with System 1 speed and expertise.

Bringing these systems of thinking back to work (again, System 1 is fast, instinctive; System 2 is slow, deliberate), not every decision we make in our business lives is equal. Some are small, relatively inconsequential, and/ or we already have lots of information about them. Other decisions are large, complex, and immensely impactful.

In Kahneman’s parlance, those small decisions are usually made using System 1 thinking – our expertise allows us to act decisively and in a way that generally leads to positive outcomes. In these cases, we are still subject to the impact of biases, but the impact is generally minimal and acceptable. For those larger decisions, we tend to use System 2 thinking by introducing more rigor and process around the decision. Introducing this formality to the process helps reduce the impact of biases by adding additional perspectives, having discussion, documenting reasons, and forcing us to take our time. So how can we make the best decision between Jane and Jill’s ideas?

HOW TO OPTIMIZE DECISION-MAKING

Take Your Time (When You Can): Some business decisions are extremely time sensitive and require quick action. In those cases, you need to build up your System 1 thinking through repetition and experience so you’re able to act quickly and with generally good judgement. Where you can, however, it is helpful to slow down, consider alternatives, and seek the opinion of others. Taking these steps can help you reduce the impact biases have on your decision-making and help assess the real impact of the decisions to be made. By determining whether the decision needs to be made right now will help ensure we’re not placing unnecessary time pressure on ourselves when in reality we can afford more complex and time-consuming thought.

Seek Education: Taking your time can reduce the impact of biases, but “reduced” is a relative term and there is room to further reduce the impact. By continuing to educate ourselves about biases, we increase the likelihood that we’ll recognize an otherwise unconscious bias impacting us, especially in our System 1 decision-making, and be able to reduce or eliminate its impact. See six common types of bias types below (business case examples and recommended solutions for each can be found in the appendix).

- Anchoring – being impacted by something else so your judgement is skewed

- Availability Bias – being biased by a recent example or memory

- Clustering Illusion – finding patterns that don’t really exist

- Focusing Effect – placing too much weight on a single event or data point

- IKEA Effect – valuing something you made more than a higher quality item you could buy

- Planning Fallacy – underestimating the time or cost of future tasks respectively

Being aware of how we are making decisions will allow us to make sure we picked Jane’s idea because it is better, not just because we like Jane better than Jill. For more information on these common types of biases and how to mitigate them, please refer to the appendix.